The Man and The Me

Read More Articles:

Christopher Spencer and His Repeating Rifle

(Originally Published in the Civil War Courier)

The Civil War was the first time in history that armies relied upon the mass production of weapons. Because of this, the process by which arms were manufactured was just as important as the weapons themselves. Christopher Spencer, a Connecticut Yankee, successfully invented the Spencer repeating rifle and later the Spencer carbine. As if that is not enough, Spencer also invented the means by which it could be manufactured. During the early years of its production Christopher Spencer had a difficult time marketing the weapon to the Ordinance Bureau; however, by April of 1864 General George Thomas called it "the most effective weapon in use."

In his youth, Christopher Spencer was a promising inventor. He studied an old issue of Comstock's Philosophy to construct a working model steam engine at the age of fifteen. In his late twenties Spencer was motoring a steam powered automobile which he designed.

His first professional exposure to the production of firearms was in the Colt works at Hartford, where he was employed as a machinist for three years. Spencer then worked at Cheney Brothers' silk factory. Here he is credited as inventing an automatic silk-winding machine that revolutionized the thread industry.

In 1860, after three years of experimentation, Spencer patented his repeating rifle. It was a good design and was rivaled only by the Henry repeating rifle, the Ball rifle and Colt's revolving rifles. However, Colt's rifles met some harsh criticism and were unfavorable by the end of the war.

With this kind of competition, Spencer needed to be a good salesman, and this he was. The rifle's design which was centered on durability could basically sell itself. The fact that Christopher Spencer had some political connections surely gave him an edge in the market. Spencer made full use of his former employer, Charles Cheney, who invested heavily in the company. Cheney was a close friend and neighbor of Gideon Welles, the Secretary of the Navy. This association was most likely the reason the Navy eventually tested the weapon.

In June of 1861 Captain John A. Dahlgren, later to become Chief of Navy Ordnance, fired some 500 cartridges. Of this large number, only one misfired and this was the result of defective fulminate. Without a single cleaning during the testing, the gun worked as well at the end of the trial as it did in the beginning. There was one concerning fact in the testing and this was that when seven shots were fired in ten seconds the barrel became threateningly hot. However, if only fourteen rounds were fired in a minute, this problem was rectified. Nonetheless, Dahlgren was impressed enough to convince Andrew Harwood, the existing Chief of Navy Ordnance, to order 700 Spencer Repeating rifles.

Then in August, at Fort Monroe, Captain Alexander Dyer fired a Spencer over eighty times. In the course of the test the weapon was buried in sand. Surprisingly, it did not clog and there were no other unfortunate side effects either. Dyer also soaked the breech mechanism in salt water and exposed it for 24 hours. Just as surprisingly the gun continued to work easily. Once again it was not cleaned during any of the tests, and it functioned just as well at the conclusion of the trial as it did during the beginning. As a result of the test Dryer said, "I regard it as one of the best breech loading arms I have ever seen."

In November of 1861, General George McClellan also did some testing. He too found the weapon to be in excellent order, saying that it was compact, durable and very accurate. However, he suggested a few improvements. For starters, McClellan felt that a chain should be added to prevent the loss of the loading tube. He also thought that there should be some spare springs for the magazine.

Despite the two great reviews, General Ripley, Chief of Ordnance, was against further implementation of the weapon. First off Ripley felt that all breechloaders were "newfangled gimcracks." Furthermore, Ripley believed that, at over 10 pounds loaded, the Spencer was too heavy. He also thought it was too expensive. Spencer rifles cost $40, or $43 for the Navy version with Bayonet. Compared to an $18 musket that could be purchased from numerous manufacturers, it was expensive. Ripley was probably most displeased with the caliber ammunition that the Spencer required. Ripley, who was largely responsible for standardizing artillery in this country, and wanted to do the same to all ordnance, thought that adding to the plethora of existing ammunition was a grave mistake.

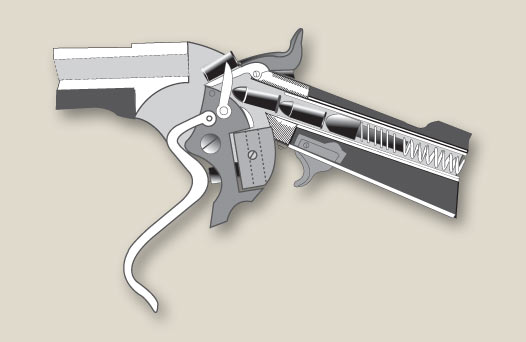

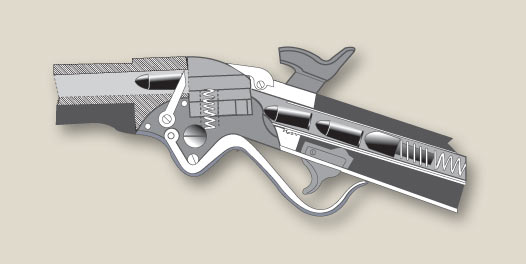

President Lincoln, who was already familiar with the weapon, stepped in. On December 26, 1861, on instruction from the President, Ripley ordered 10,000 Spencer Repeating rifles. 500 of them were to be delivered in three months. The armed forces found the Spencer to be an excellent weapon, even though it had a great deal in common with its competitors. The Spencer, along with its rivals, was designed around a metallic, self-contained cartridge. The ammunition for all the early repeaters was fed from a spiral spring tubular magazine. The repeaters all used a lever, which doubled as a trigger guard, to eject their spent cartridge cases and chamber the next round. To do this the lever operated a movable breechblock or bolt. All three of the major designs were fundamentally stable. However, the military's choice of a repeater was made in regards to its strength, power, and durability.#

Where the Spencer excelled beyond its competition was in its sturdy design. However, sturdy design did lead to certain disadvantages. The Spencer's magazine was located in the butt stock. This element of its design surpassed rival manufacturers in safety because it left the magazine spring concealed. Even so, this added safety cost the rifle quick and easy loading. The frame and breech block of the Spencer were stronger than the competitions' versions. Yet this also had the down side of greater overall weight. The Spencer fired a heavier bullet in a .56 caliber cartridge with a heavier powder charge. Although this gave the gun more power, soldiers were unable to carry as much ammunition due to the greater weight.

The Spencer had two certain disadvantages as compared to the Henry Rifle. One of these was that the Henry's magazine held sixteen shots to the Spencer's seven. The other was that the Spencer did need to have its hammer thumb cocked every time it was fired; while the Henry's hammer was cocked in the action of pumping the lever.

The Spencer was still more rugged than all of its competitors, and this was the most important thing to the soldier of the day. Even more important, in a time when arms were in continuous demand, Christopher Spencer managed to produce weapons faster than his competition.

Even with his connection to the Secretary of the Navy, potential arms manufacturers had flooded the market, Spencer and his chief business associate Warren Fisher, needed to be able to market the idea that they could produce a momentous number, in a short period of time, at a relatively low cost. This was when Spencer's experience as a machinist paid off.

It is important to note that the weapons the Navy, and most likely the Army, tested were only hand tooled mock ups. In June of 1861 the Spencer Repeating Rifle company was really in no position to be able to mass produce them.

Spencer and Fisher first needed to find a residence for their operation, and fast. The Spencer Repeating Rifle Company set up shop in Boston where they rented the second floor from the Chickering Piano Company on Tremont Street. Spencer's gifted understanding of the technical principles of production and his ability to problem solve, allowed him to find ways of cutting production time. He was able to mass produce his weapons because he specialized in one style of arm. Although this paid off in the end, it was a very risky investment. In fact, if the company folded in July of 1861, $75,000 would have been lost in machinery alone.

Spencer recognized that specialized machinery was important. Yet, he also understood the importance of skilled labor. The Spencer Repeating Rifle Company hired workers from all over the country for their superior skill. They would often have to be enticed away from other lucrative positions with the promise of better pay.

Still, with all of Spencer's knowledge and ability, the three month delivery for the Armies weapons was basically impossible. To make matters worse for the company, Lincoln replaced the first Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, with Edwin Stanton. Stanton was quick to evaluate the problems left behind by his predecessor. One of these was a large outstanding deficit in unfulfilled arms contracts. This meant big trouble for the Spencer Repeating Rifle Company. In May of 1862, when the company's contract was evaluated, it was 2,500 rifles behind scheduled delivery. That is to say they had not delivered a single arm for the months of March, April or May. The Spencer Repeating Rifle Company was lucky. The total order was scaled back to 7,500 and the date of the first delivery was rescheduled to July 6. The Naval contract was not affected by the change of staff in the War Department. Still, it's order arrived just as late as the Army's.

On December 4, 1862, the arms for the Navy contract were finally completed. They were delivered to the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston, during February of 1863. On January 31 of 1862 the first 500 Army rifles were delivered. By then the Army contract was 6 months late for its rescheduled deadline. The Spencer repeating rifle company had difficulty meeting its deadlines for several reasons. The first was difficulty in obtaining or creating new machinery. The second reason was that there was a shortage of skilled machinists. The final reason stems from Christopher Spencer himself. Spencer was much more concerned with the perfection of his rifle than the nuances of time, money and delivery deadlines. Fisher was soon regretting his decision to make Spencer, the gun's inventor, responsible for its manufacture. In a time when the company was falling farther and farther behind deadline on a large military contract, Spencer was more concerned with patenting his improvements to the caliber of the rifle. He reduced it to .50 caliber.

Spencer's concern for the perfect weapon also led to his change of position in the business. He soon sold his patent rights to the company for a royalty of $1 per gun sold. This does not mean that he no longer did anything to help the company prosper.

With the Federal orders finally catching up, Spencer used his time to further market the weapon. He took a tour out west and personally demonstrated the proper use of the rifle to the armies. Although all of his visits were favorable, only one brought forth a direct sale. This was an unusual sale at that. Col. John T. Wilder's brigade of mounted infantry was so impressed with the Spencer that the enlisted men promised to pay for it out of their own pocket. Wilder, a successful business man himself, cosigned the order. This was another serious risk for the Spencer Repeating Rifle Company because it meant that the weapon would not be paid for on delivery. Instead the company would receive payment as the soldiers got their government checks. The Ordnance Department later picked up the tab and Wilder got his men's precious rifles through regular issue.

It turned out to be an excellent investment for both Wilder and Spencer. On June 24, 1863 Rosecrans ordered Wilder's 1st Mounted Rifles to "trot through" Hoover's Gap. Wilder paid no attention to the Confederate rear guard as his troopers pushed their way through numerous Confederate pickets. Finally Bushrod Johnson was ordered to maneuver his brigade against Wilder's men. Even so, Wilder's troopers, fully utilized their Spencers and managed to hold their ground. In the battle, Wilder lost 51 men as compared to Johnson's 145. As a result of this engagement the 1st Mounted Rifles became known as Wilder's Lightning Brigade. More importantly for the Spencer Company, the weapon had proven its effectiveness.

In June of 1863, the last of the Army's rifles were being delivered. By this point the Spencer Company was producing around 1,500 rifles per month.

Spencer's most important client was the President of the United States. Even with the weapon's proven effectiveness, Mr. Lincoln had personally stopped the issue of the Spencer to some units. There were two causes for the President's actions. One was because Lincoln had given Hiram Berdan, commander of the Sharp Shooters, a Spencer to test. Tragically, the weapon misfired and temporarily blinded Berdan. Another reason resulted from Mr. Lincoln's disappointment with the performance of two Spencers which had been given to him by the Navy. Mr. Lincoln was unable to load the first model that he was given. This was most likely because it had a rusty magazine tube. The President then attempted to fire the second rifle. When he fired this gun it locked up on him. This stemmed from a double feed which was an easy mistake to make with the Spencer repeating rifle. It happened when the gunman did not handle the lever smoothly.

Spencer paid the president a visit in August of 1863 to demonstrate to him the proper use of the weapon and explain the problems and their solutions. The next evening they apparently met at the Washington Monument. They then walked to the Treasury Park where they spent an hour firing a Spencer Rifle. The actual target for this shooting competition between Christopher Spencer and Abraham Lincoln can be found in Springfield Illinois. The meeting was successful, as the president never stopped the guns distribution again.

However, he never increased the orders either. In July of 1863, due to great demand, the Spencer Repeating Rifle Company produced carbines for the first time. This was because the rifles were too heavy and difficult to handle for mounted service.

Additionally, the rifle had no sling ring, so if a cavalryman dropped it, the weapon could be easily lost. About the same time as the Lincoln meeting, the Spencer company then approached the War Department with the idea of producing carbines. The War Department quickly accepted the offer and a contract was written for 11,000 guns to be delivered before the end of the year, at a cost of $25 per unit.

Although the order was filled late as usual, it was not nearly as bad. 7,000 carbines were delivered by the year's end and instead of reducing the order, the War Department ordered more. Before the first contract could be completed the quantity was increased to 34,500.

Meanwhile, the Spencer Repeating rifle continued to prove its value. In September, in Northern Georgia, near a stream named Chickamauga the Confederacy felt the full effect of the Spencer for the second time. Longstreet's corps pushed on across an open field. Suddenly, they heard a frightening new sound. A steady thunder and downpour of fire and lead. Longstreet's men had just met the Spencer Repeating rifles of Wilder's Lightning Brigade. "The head of the column, as it was pushed on by those behind, appeared to melt away."

The Confederates managed to find shelter in a drainage ditch which ran along the field. This was to no avail because two 10-pounders poured double-shot canister into the Rebels ranks. Col. Wilder said, "They fell in heaps, and I had it in my heart to order the firing to cease to end the awful sight." However, he gave no such order, and when it was over, "one could have walked for two hundred yards down that ditch on dead rebels without touching the ground."

Once again the Spencer had proven its value. Because of Wilder's Lightning Brigade's accomplishments Spencers became highly sought. However, there were some disadvantages to holding a Spencer. The 63rd Pennsylvania were glad to turn in their old Austrian muzzle loaders for Spencers in 1864. When they began to hear the orders "Spencers to the front" it turned out not to be such a great bargain.

Still, most people wanted to get their hands on them. General Ramsay wrote of the carbine, "The demand for them is constant and for large quantities. It seems as if no soldier who had seen them used could be satisfied with any other."

To accommodate the great demand for the carbines, which were more popular than the rifles due to their lighter weight, contracts were made to the Burnside company. However, deliveries of the additional 30,502 carbines M1860 made by the Burnside company were not carried out until the end of the war. Therefore, none of them were actually used before the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered.

In 1869, because of the huge surplus that it had created, the Spencer Company was forced to close its armory. It was bought by the Fogerty Rifle Company, which was later purchased by Winchester.

Christopher Spencer's last contribution to the world of manufacturing was by no means the Spencer Rifle. He went on to design an unsuccessful shot gun. However, this failure did not undermine his success in patenting the first automatic screw manufacturing machine. He also started several companies, the most successful was the Billings and Spencer Company. This company helped to create safe boiler designs. At age 89, before his death in 1922 he was able to take flying lessons. Spencer's invention, and his production techniques were in part responsible for bringing an end to the Civil War. Even with all the hassle that he received from Ripley, a good design was able to prevail. Without Ripley's distrust for breech loading weapons, could the war have been ended any sooner? No, it is probably most fortunate that Ripley was opposed to the Spencer, for if the contracts had been any larger, the company would have most likely folded in May of 1862.

References

Lincoln and the Tools of War, by Robert V. Bruce, 1956. Bobbs\Merrill Company Inc., New York , NY

The Book of Rifles, by W. H. B. Smith and Joseph Smith. 1972 Stackpole Company Harisburg, PA 17105

The Union Cavalry in The Civil War Vol. I, II, III, by Stephen Z. Starr. 1979 Louisiana State University Press#